Abstract:

Plato's Dialogue 'Euthyphro' (pronounced yu-thi-fro) delves into moral philosophy, probing into the intricate questions surrounding morality, piety, and the nature of the divine. Through the dialectical exchange between Socrates and Euthyphro, the dialogue navigates through the complexities of defining piety, ultimately challenging conventional wisdom. This discourse aims to reflect on the complexities of righteousness, piety and morality. By analyzing the arguments presented in the dialogue, we seek to make efforts at grasping the elusive essence of ethics.

1. Introduction:

The Dialogue spans approximately 20 pages, comprising a dynamic exchange between Socrates and Euthyphro, interwoven with numerous examples and discussions aimed at substantiating their respective arguments. In the interest of brevity and to focus on key points, we will stick only with the gist of it. However, it is highly recommended to read the full version for more clarity and exploration in this subject.

Link to one of the sources: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1642/1642-h/1642-h.htm

Socrates encounters Euthyphro, an Athenian (not much is known about Euthyphro, but it is apparent from the Dialogue that he was a priest and considered himself a pious one at that) outside the court where Euthyphro is prosecuting his own father for impiety.

Euthyphro's family had a servant who, in his drunken state, killed one of their household slaves. For this crime, Euthyphro's father had his hands and legs tied and thrown into a ditch, concurrently, sending a messenger to a nearby priest to consult for an appropriate course of action over this. Before the messenger returned, that servant died due to cold, hunger and being in bound state, which Euthyphro claimed, was due to his father's negligence which in turn was due to the servant's criminality.

Euthyphro claims that in prosecuting his father for his wrongdoings, he was being utmost pious, while the rest of his family viewed his actions as impious, denouncing him for prosecuting his own father in defense of a killer.

Socrates himself was attending on that day, being indicted by an individual named Meletus, on charges of corrupting youth with his "ungodly" ideas (a little side-note: Euthyphro is first of the four Dialogues which deal with trial and death of Socrates). Intrigued by Euthyphro's seemingly profound understanding of piety (we will refer to this notion of piety interchangeably as righteousness or an action done for good or a moral act), Socrates engages him in a conversation aimed at unraveling the true essence of this concept. Throughout the dialogue, Socrates employs his signature method of elenchus, or cross-examination (elenchus is the Socratic method of eliciting truth by question and answer, especially as used to refute an argument and we can today see the same being applied in fields of sciences, logic, philosophy, etc.) to probe Euthyphro's definition of piety.

2. Questions

(Following questions are chief points of discussion but not the only ones asked by Socrates during his inquisition)

Question #1: What is piety (in essence)?

At first, in reply to Socrates' enquiry, Euthyphro asserts that piety is something synonymous with what is loved by the gods (in those times, one could even be executed if they did not believe in multiple Greek Gods), implying that actions pleasing to the divine are inherently pious. This resonates with traditional religious beliefs, which often equate morality with divine command. Socrates proceeds to show the error in this plain statement by stating that the gods are not all in agreement with one another in all matters. There's discord amongst them and surely their points of differences must also be not some typical lighter issues, but must be on issues of what is good and bad, just and unjust, beautiful and ugly. Euthyphro agrees it must be so to which Socrates says, then the pious and impious are subjected to different opinions of different gods, and thus love of gods itself cannot be an essence of righteousness.

Further on when prodded more on this, Euthyphro says what all gods love is pious and that which all gods hate is impious.

Question #2: Are actions pious because the gods love them, or do the gods love them because they are pious?

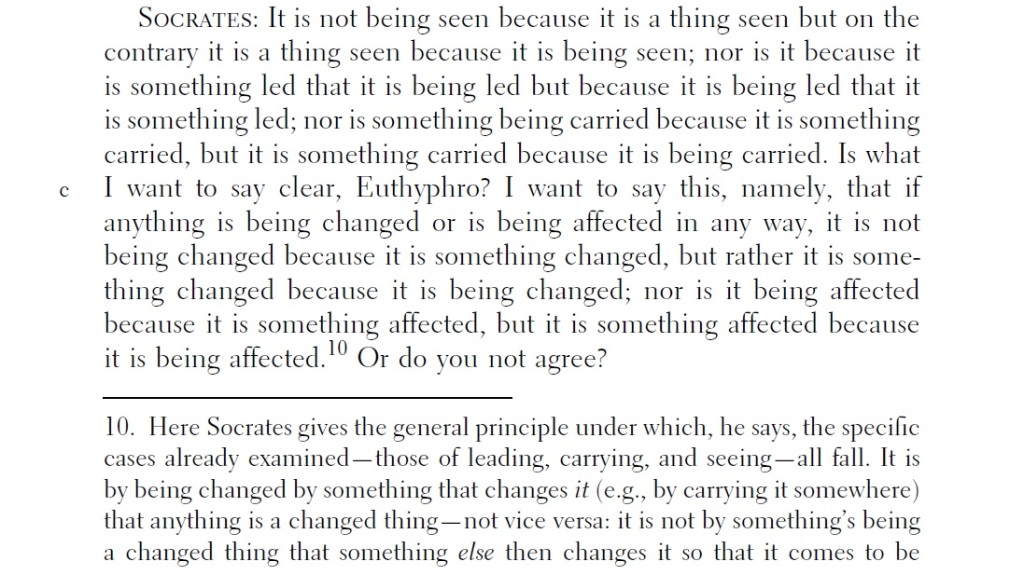

Socrates' probing reveals the limitations of this perspective.

He nudges Euthyphro into getting to a correct perspective to this question by giving examples on something which must be explanatory priority ('explanatory priority' refers to the principle in philosophy, science, and other fields that some explanations are more fundamental or primary than others. It suggests that certain aspects of reality or phenomena can be explained in terms of more basic or foundational principles, which serve as the starting point for understanding other phenomena).

While reading and understanding the argument in the image above might take up significant time, we would give an example in line with Socrates' argument:

We say 'rose is red'.

Does it imply our saying rose is red makes it red (assuming colors are unnamed yet and when you say red, we assign that name to rose's color)

OR

Is it that since rose is red, we say 'the rose is red'? (in this case we assume already naming the color prior to looking at the rose)

Clearly, in the above, our assigning of any name to the rose's color doesn't affect the color it is originally. Hence, there's explanatory priority that rose is of a certain color whatever it is and that we call it red after naming that color so. Our assigning a certain name to that color has no impact on the rose's appearance.

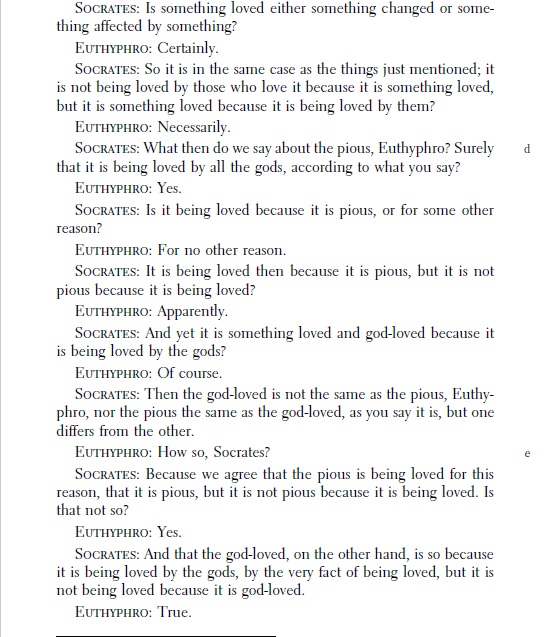

Similarly, Socrates explains that some actions are pious actions not because they are being loved by gods, but because they are already pious and so subject to love of gods.(corroborating with example we mentioned, loving has no impact on an action which inherently is already righteous).

Question #3: Is it that where there's justice, there's piety or is everything that is pious always just?

To resolve Euthyphro's confusion about what was being asked, Socrates gives an example:

It is not right to say where there is fear there is also shame, but it is correct that where there is shame there is also fear, for fear covers a larger area than shame. Shame is a part of fear just as odd number is a part of numbers, with the result that it is not true that where there are numbers there is also oddness, but that where there is oddness there is also number. With this, he questions Euthyphro if this is a correct way to look at it: where there is piety there is also justice, but where there is justice there is not always piety, for the pious is a part of justice. To this, Euthyphro says it appears correct how Socrates put it. Socrates dwells further on this, trying to get to the crux of piety within justice by saying that just like in a set of numbers if a number from it is defined to be an even number, one could easily define it as the one which is divisible by 2. Then he beseeches Euthyphro to give him such a concrete definition for piety too (a sub-set) within justice (main set).

Question #4: What part of justness constitutes pious?

Euthyphro answers: "I think, Socrates, that the godly and pious is the part of the just that is concerned with the care of the gods, while that concerned with the care of men is the remaining part of justice."

Socrates requires more information on this. He says men care for their cattle, dogs, horses. Does that mean godliness and piety is caring for gods? Yes, says Euthyphro. The further conversation is about Socrates making a point that while caring by men for an object of care is in order to benefit that object in some way, similarly, if a view is taken that piety or godliness or actions as such which are pleasing to gods that is making sacrifice to and prayers done for them, do in some way benefit the gods? After some more questioning as to the nature of worshipping to gods and whether we are gifting gods when we perform those actions to benefit them in some way, Euthyphro replies that it doesn't benefit gods but are pleasing to them.

Thus the argument comes full circle from where it began! That if piety is made of actions that please gods or that gods love those actions which are pious, the nature of piety as to why it is so still remans unclear.

Euthyphro now evades Socrates' inquistiveness saying he's gotta go. Maybe some other time!

3. Divine Command vs. Objective Morality:

If actions are deemed pious simply because the gods love them, then morality becomes arbitrary, contingent solely upon the whims of the divine. This notion challenges the basis of ethical reasoning by many faiths and cultures, suggesting that there exists no objective standard by which to judge the righteousness of actions. On the other hand, if actions are pious, independent of the gods' approval, then the divine loses its authority as the arbiter of morality. This alternative proposition aligns with the concept of objective morality, positing that certain actions are inherently right or wrong regardless of divine (Gods') endorsement. While this perspective offers an alternate foundation for ethical reasoning, it raises questions regarding the origin and nature of moral principles. Hence, we are faced with two distinct conceptions of morality: divine command theory and objective morality. Divine command theory asserts that the moral rightness of actions is contingent upon divine approval, rendering morality subjective and dependent on the whims of the God(s). In contrast, the concept of objective morality posits that moral principles exist independently of divine will, grounded in universal truths that transcend the divine realm. This particular comparison might however be limited to this Dialogue of Plato, as further concepts and theories of Plato offer more depth and understanding into the complexity of essence of morality.

4. Conclusion:

Plato's Dialogue 'Euthyphro' stands as a timeless testament to the enduring pursuit of wisdom and truth in the realm of moral philosophy. The purpose of the dialogue is also, in part, to showcase correct methods of thinking, especially the dialectic method. As we continue to engage with Plato's profound dialogue, we are reminded of the perennial significance of philosophical questioning in our quest for understanding and enlightenment. While the dialogue may not offer concrete answers, its enduring relevance lies in its ability to spark introspection and inspire a philosophical inquiry.

Defining piety is indeed a complex issue. Let's see what we can derive from the discourse above. The first and foremost definition of piety given by Euthyphro is that it is loved by gods and furthermore, something loved by all gods. It would be indeed rare in the current times for this definition to resonate. When we try to compare this or change it in view of only one God/Creator, assuming most religious or non-religious people (excluding atheists) would believe in one God or a certain Universal Power. This changes a lot of arguments above from our viewpoint. There's no issue of multiple gods in disagreement with what actions they love (or hate).

Next, let us consider whether piety is itself something to be loved or is it loved because it is pious? Here, we can consider that a pious act (according to own standards and in comparison to the universal morality) will always be loved by God no matter how small it is. While for some, it's the intent of doing good regardless of the outcome, and for some it's the outcome of good regardless of the process. Whichever it is, we do believe it is not God's love for such an action that makes it pious, but it is the goodness in the action itself.

This will get complex when we consider theories of objective morality, relative morality, what is supposed to be good and from whose perspective. Before discussing about the source of good, we can agree that much of what we believe to be good comes from factors such as our culture, faith, regional laws, upbringing, readings of holy scriptures and values cultivated in ourselves with the growing in age and what mindset or thought process is applied (which changes with life experiences). A very small example is that, in some cultures, consumption of all kinds of alcoholc drinks is considered an impious act while in others, an alcoholic drink like wine is encouraged. Regardless of this, a person may or may not choose to follow what the culture professes.

What actions become good also depend on a person's internal feelings, circumstance, discipline in life, emotional sensitivity, and a plethora of such other factors. Hence, it largely and very variedly differs from person to person. While a sane person would refrain from harming others, a psychopath might lack such a thinking. At times, an action felt good in the heat of the moment might then become a source of endless guilt and remorse. All of these points imply that a soul is incapable of making sense of right from wrong. Even more so at higher levels and with increase in complexity of actions.

But, this is also a fact that a soul (not only human's, but of other living beings as well) is endowed with a potential to learn and identify actions for it's own good.

With these points made, it is now out of scope for this paper to discuss other advanced concepts that shed light over this subject and start to delve deeper into the core of abstract notions.

5. Some questions to ponder and think deeply over:

a. What did you make out from the discourse above?

b. What is at the core of piety or righteousness according to you?

c. Consider a hypothetical situation wherein a long known friend of yours whom you lost touch with some years ago has committed a heinous crime. The court in your land has passed judgement to hand him a death sentence, fearing that the person in question would be dangerous for the society. You have contacts and possess power to get your friend out from his confinement in the dark of the night and send him far away.

c.1. What would you choose to do?

c.2. Can adhering to the law of the land be considered piety and should be prior to a long friendship? Would you decide to follow the judgement passed even if instead of a friend, he/she was your own child?

c.3. Should you disagree with the judgement passed and choose to oppose according to your definition of impiety?

c.4. Should you choose to let your friend escape and send far away (you felt that your friend would repent and become a good man if given another chance), if your friend goes to another place and gets involved in another crime, would you feel responsible for the consequences of your action? Or that the intent and action of piety cannot be applicable for a separate incident?

6. Additional Notes:

Plato was a devoted student of Socrates and he greatly expanded upon Socrates' ideas after Socrates' death. Plato founded his Academy in Athens, which became one of the most famous philosophical schools in ancient Greece. He had numerous disciples, including notable figures like Aristotle, who were drawn to his teachings and philosophical inquiries, who at the time were curious about the concepts and philosophies Plato brought forth (also in part, such following of Plato might also be due to the kind of constricted philosophies of the past and disagreements amongst the citizens then). Plato's work represents a significant development in ancient Greek philosophy and has had a profound influence on Western thought.

Plato developed Theory of Forms (it's important to note that Plato's works cover a wide range of topics beyond just this theory), which posits that the material world is only a shadow or imperfect reflection of the true reality of Forms or Ideas.

Such a theory was further in time refined and corrected by one of Plato's disciples Plotinus who laid the foundation of the Neoplatonic philosophy. This was a profound theory which impacted further philosophical explorations to an extent not seen before. It was incorporated in Christianity by Christian philosophers of the time to explain Trinity and other esoteric concepts. Christian Neoplatonism contributed to the development of Christian mysticism, theological reflection, and understanding of metaphysics.

Some more decades later, in the Islamic golden age, a lot of Muslim philosophers engaged with this theory in a complex and multifaceted way and corrected elements in it (from their perspective), in line with Quranic concept, under the guidance of the Imams of the era and seeking knowledge from them, integrating Islamic theology and thought into their philosophical works, developing it further.

All of these developments, modifications and corrections in theories seeks to expand the human knowledge and answer the myriads of questions at core of our existence; the question of piety being one of them.

It is not Al-Birr (piety, righteousness, and each and every act of obedience to Allah, etc.) that you turn your faces towards east and (or) west (in prayers); but Al-Birr is (the quality of) the one who believes in Allah, the Last Day, the Angels, the Book, the Prophets and gives his wealth, in spite of love for it, to the kinsfolk, to the orphans, and to Al-Masakin (the poor), and to the wayfarer, and to those who ask, and to set slaves free, performs As-Salat (prayer), and gives the Zakat, and who fulfill their covenant when they make it, and who are As-Sabireen (the patient ones, etc.) in extreme poverty and ailment (disease) and at the time of fighting (during the battles/wars). Such are the people of the truth and they are Al-Muttaqun (pious).

***

Sources

Book 1: Five Dialogues, translated by G.M.A Grube

Book 2: Plato – Euthyphro Apology Crito Phaedo Phaedrus, translated by Harold North Fowler

Images:

- Original Greek version of the Dialogue, book: Plato – Euthyphro Apology Crito Phaedo Phaedrus, translated by Harold North Fowler

- ‘Are actions pious because the gods love them, or do the gods love them because they are pious?’, book: Five Dialogues, translated by G.M.A Grube

- Socrates’ method of elenchus, book: Five Dialogues, translated by G.M.A Grube

- The Death of Socrates, painting by Jacques-Louis David, http://www.history.com

- Plato (c. 427 BC – c. 347 BC), https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/contributors/plato

- Surah Al-Baqarah, verse 177, https://corpus.quran.com/translation.jsp?chapter=2&verse=177

—